Challenges to Democracy: Backsliding and Autocratization

This piece originally appeared in the 2023 Princeton Int'l magazine. Read the magazine here.

Democracy is under stress in long-established democracies and authoritarian politics is on the rise. This trend contrasts with recent history. The world experienced its longest and deepest democratic wave in recorded history, at various points in the second half of the 20th century. In the post-World War II period, Europe transitioned to a democratic region following the challenges of fascism and traditional authoritarian regimes in much of that region in the interwar period. In turn, the world began to experience the third wave of democracy in Europe’s Iberian Peninsula in the mid-1970s, with geographic spread throughout the globe during the rest of the 20th century: Latin America in the late 1970s to early 1990s, affecting the entire region, save Cuba; parts of Africa, where many countries transitioned to competitive multiparty elections; and political openings in Eastern Europe following the collapse of the Soviet Union. In the early 21st century, the world also witnessed the short-lived Arab Spring in parts of the Middle East. Liberal democracy was ascendant, and some optimists proclaimed that we were at the end of history.

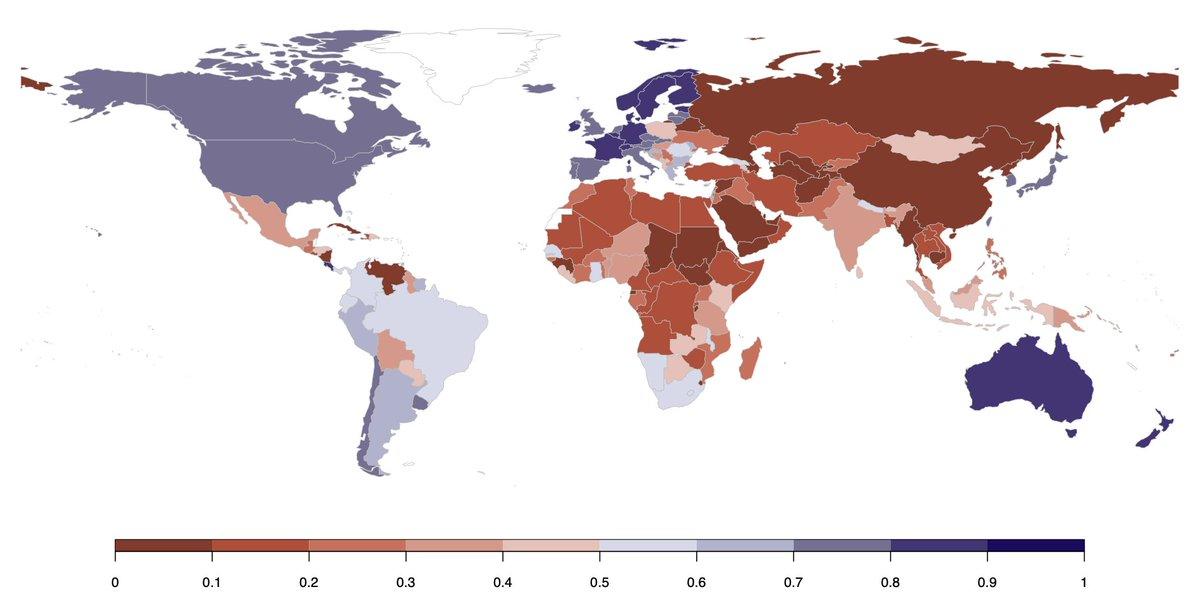

Recent political developments in the Global North and Global South are sobering and highlight the increasing challenges to democracy. Indeed, democratic backsliding has become more common — oftentimes hollowing out democracy from within, as professor emerita Nancy Bermeo noted early on in her now classic 2016 Journal of Democracy article, “Democratic Backsliding.” The Varieties of Democracy Project (V-Dem) has become an unparalleled resource in tracking regime politics around the world, using a four-part scale of regime type: closed autocracy, electoral autocracy, electoral democracy, liberal democracy. In V-Dem’s Democracy Report 2023, they have shown that liberal democracies peaked in 2012 and have since returned to 1986 levels. According to V-Dem, “Advances in global levels of democracy made over the last 35 years have been wiped out.”

Indeed, if liberal democracy seemed ascendant in the 1980s and 1990s, autocratization (both through electoral and coercive means) is ascendant today — posing existential political challenges around the globe. V-Dem’s Democracy Report 2023 indicates that countries are evenly split, with 89 democracies and 90 autocracies in the world. Yet these numbers belie several important facts.

First, even within the democratic camp, the number of liberal democracies is on the decline. Today only 13 percent of the world’s population resides in a liberal democracy.

Second, most of the world’s population now lives in autocratic countries, since autocratic countries are far more populous than democratic ones, with 72 percent of the world population — 5.7 billion people — living in closed or electoral autocracies, according to V-Dem.

Third, if both electoral and closed autocracies are on the rise, the latter is more common, with a plurality, some 44 percent of the world, living under such a regime.

Fourth, autocrats are often deploying and capturing traditional democratic institutions to make autocratic moves. For example, anti-pluralist parties are often driving autocratization, according to an earlier 2022 V-Dem Democracy Report, in places like Hungary, India, Poland, Serbia, Turkey, El Salvador and Brazil (although Brazil’s 2022 election reversed this authoritarian course). In these cases, governing parties have taken the lead in eroding liberal institutions and challenging freedom of expression by slowly and steadily attacking the courts, censoring the media and repressing civil society organizations, academics and cultural organizations. These concerns have also manifested in longstanding democracies, most notably the U.S., where the Jan. 6 insurrection emphasized the coordinated (if unsuccessful) challenges to democratic institutions and norms.

Indeed, news of illiberal politics and coercion are once again common in today’s news: insurrection in the United States, with copycat efforts in places like Brazil; violation of civil rights in the Philippines; invasions by Russia into Ukraine; delimitation of court powers in Israel; military coups in Gabon; imprisonment and exile of dissidents in Nicaragua; the list goes on. The political imaginary includes those who advance democratic and autocratic ambitions, sometimes using elections in both cases to advance such goals.

To understand these challenges, Princeton faculty, fellows and students came together this past year — via scholarship, courses and public events. Princeton has hosted many related events to address democratic backsliding and autocratization, including through PIIRS’ Global Existential Challenges Seminar series and Brazil Lab as well as SPIA’s Afghanistan Lab. The Constitutionalism Under Stress project (CONSTRESS), supported by the Princeton-Humboldt Strategic Partnership, has also organized graduate training and workshops to explore these challenging issues, especially in Europe.

At Princeton, there have been efforts to understand how we can hold up the guardrails of democracy and claw back against autocratic moves. On the latter, we take inspiration from leaders such as Nobel Laureate Maria Ressa ’86, who, as a leading journalist and founder of Rappler.com, has written and spoken about the centrality of freedom of expression and the need to stand together against dictators who violate such rights. Her recent book was assigned as the Pre-read for incoming students. Indeed, President Christopher L. Eisgruber has placed a premium on freedom of expression and this fall invited both Ressa and ACLU Executive Director Anthony Romero ’87 to speak about this fundamental right.

Dora Maria Tellez (PLAS-PIIRS-SPIA visitor in summer 2023) has also demonstrated the courage to fight against dictators — starting in the 1970s she heroically fought against the Somoza family’s 43-year dictatorship in Nicaragua and later worked to forge a democratic alternative to her former Sandinista comrade and now autocratic president, Daniel Ortega. As a result of that activism, Tellez was placed in solitary confinement before being stripped of her of her nationality and citizenship, as were over 200 other political opposition leaders. Her colleague, Sergio Ramírez, a politician and novelist now living in Madrid, has also visited Princeton on several occasions; importantly, he has bequeathed his archives to the library for future generations to learn about the art of politics and culture in forging a more democratic future. We have much to learn from those who have the courage to stand up in the face of coercion and uncertainty — speaking out and organizing publicly to defend freedom of expression, the integrity of the vote, the centrality of the rule of law, among other democratic freedoms and rights. This issue focuses on how Princeton has set out to understand challenges to democracy and the efforts to uphold it.