Converging Currents: Gender, Sustainability, and Governance Through the Lens of CGI Spring 2025 Visitors

This spring semester, In hosting four multidisciplinary visitors, M.S. Chadha Center for Global India (CGI) turned Princeton into a crossroads where India’s most urgent ideas met the campus community, allowing distinct voices to frame how we think about artistic expression, ecology, policy, and work.

At the start of the semester, poet and activist Meena Kandasamy took the stage to read from her uncompromising new collec

tion, Tomorrow Someone Will Arrest You. Kandasamy treats poetry as a form of insurrection, one that refuses to let institutional silencing machinery muffle individual experience. The titular poem — written after two close friends were arrested under the Unlawful Activities Prevention act — sets the tone for a book that braids sensuality, domestic life, and militant dissent with unflinching clarity. During her talk, Kandasamy parsed the way everyday acts of intimidation, caste hierarchy, and gendered violence accumulate into the headline events we label “history. ”By turning those quieter infringements into lyric moments, she argued, a poem can expose the scaffolding of oppression that often hides in plain sight. Moving seamlessly from personal desire to refugee crises, from family intimacies to public protest, Kandasamy demonstrated how the private and political are inseparable—how a single, well‑aimed stanza can widen the space for solidarity and resistance.

Kandasamy confronted power head-on, while our following visitor let societal fault lines simmer at the edges of his frame. In March, CGI welcomed Shaunak Sen to feature a screening of his award-winning documentary, All That Breathes. The film, which garnered the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance, Best Documentary at Cannes, and an Academy Award nomination, intimately

portrays two brothers who run a makeshift basement hospital in crowded, polluted New Delhi, dedicated to rescuing injured kites. These majestic birds of prey, vital to Delhi’s ecological balance, increasingly fall victim to the city's worsening air quality and urban obstacles. Sen initially envisioned the film primarily as a narrative about care and interspecies connections, but he found himself unexpectedly documenting the emotional complexities between the brothers and the turbulent backdrop of social unrest in Delhi. In a conversation with CGI’s Acting Director, Prof. Gyan Prakash, Sen offered an intriguing glimpse behind the scenes, describing how he spent extensive time with the brothers over three years to make the film. Long hours were spent

in front of the camera until a key factor allowed the brothers’ authentic selves to emerge—boredom. Sen recounted working hundreds of hours of footage to find within them a compelling story, and highlighted the subtle interplay of humor to alleviate the seriousness of socio-ecological crisis.

CGI continued the spotlight on sustainability, shifting from a cinematic lens to a governance-focused framework. Ritu Sain,

Indian Administrative Service officer and CGI’s month-long visitor in April, was the innovator behind India’s first zero-waste city, Ambikapur. Arriving at Princeton to draft a white paper documenting the project, she engaged faculty and students across disciplines, including public policy, engineering, and biotechnology. As district magistrate of Ambikapur in 2014, Sain inherited a city overflowing with garbage and public health issues. She was met with more than 20 uncontained dump sites, a 24‑acre, 20‑foot‑high landfill, and a budget‑draining, contractor‑run dump system. Rather than replicate high-tech fixes ill-suited to a small, resource-constrained city, she developed a decentralized system built on daily door-to-door collection by women in organized self-help groups and strict household-level waste segregation. The collected waste is then taken to 20 neighborhood

resource-recovery centers, where teams of women oversee detailed secondary and tertiary sorting, operate low-carbon electric rickshaws, and log data to ensure transparency and efficiency across the system. Today, the scheme meticulously recycles or composts every single piece of its waste, returning it back to the economy. It employs nearly 4,500 women from vulnerable communities, and has been adopted in 168 cities across the state of Chhattisgarh—transforming a public-health crisis into a model of climate resilience grounded in dignity of labor. In class visits and workshops, Sain urged students to see waste as a climate threat and governance opportunity, and to build climate resilience “from below” through locally-rooted, inclusive policy, as well as human‑centred design.

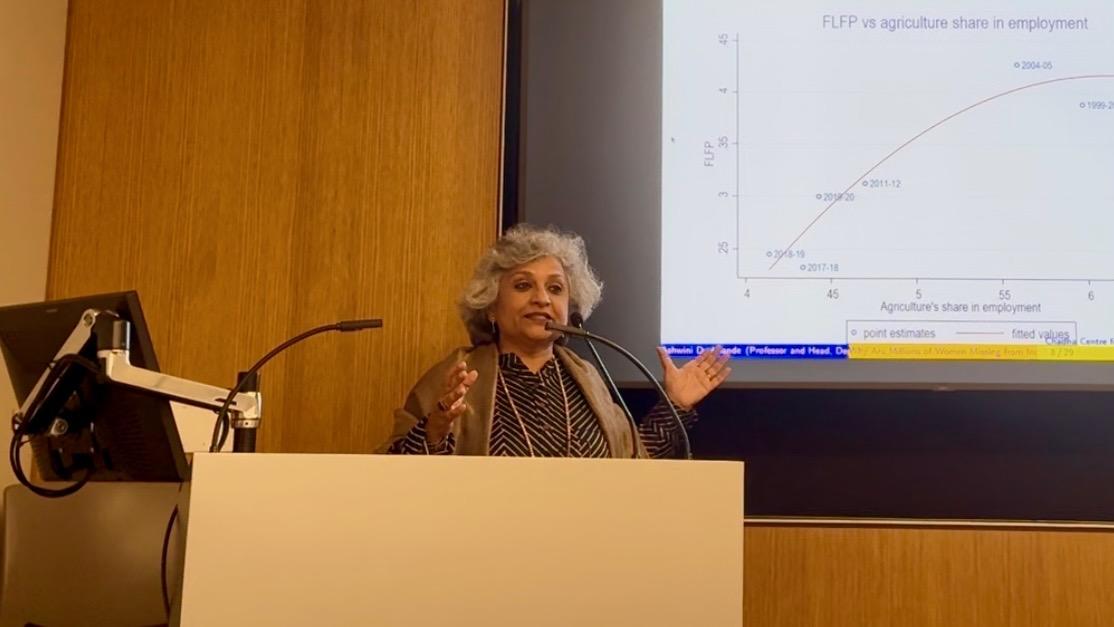

To deepen the gender-and-work conversation sparked by Sain, CGI welcomed its final guest: Ashwini Deshpande, Professor

and Head of the Department of Economics, as well as Founding Director of the Centre for Economic Data and Analysis at Ashoka University. At her keynote talk, “Why Are Millions of Women Missing in India’s Workforce?” she laid out a central contradiction in India’s development story: female schooling and GDP have risen sharply since the early 1990s, yet women’s share of paid work first slid below 30 percent and has only recently inched back toward 40. That slump coincided with structural change in the economy, signalling that rising GDP and schooling have not automatically converted into wider economic autonomy for

women. Using Indian survey evidence and international parallels—including Claudia Goldin’s long-run work in the United States—Deshpande argued that the problem is less about women’s willingness to work than the economy’s failure to create enough jobs they can realistically take. Heavy unpaid care burdens and caste- or region-specific norms restrict hours, but women enter

the labor market whenever viable, dignified work appears. The policy imperative, she concluded, is to expand demand—especially in non-agricultural sectors—while investing in childcare and safe transport, allowing opportunity itself to erode restrictive norms and bring India’s “missing millions” into the workforce.

The semester’s dialogue affirmed CGI’s founding purpose, demonstrating that situating India within a global conversation expands our collective imagination and equips us to pursue human and planetary well-being. Across the four visits, participants left with concrete insights that they can now test and translate into their own communities around the world.