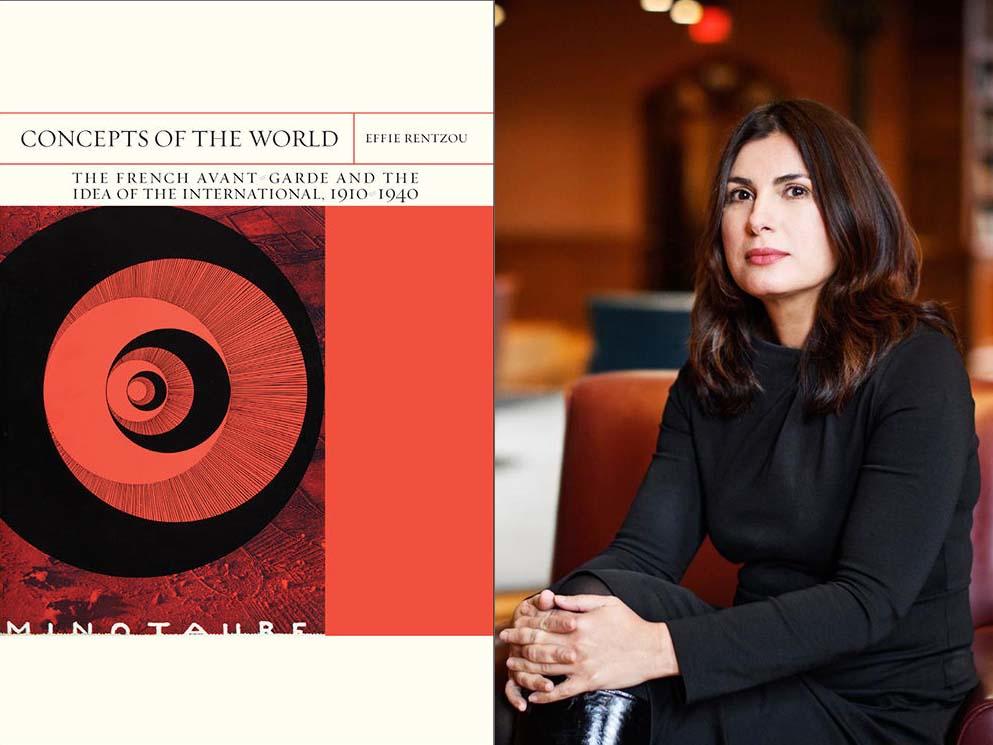

Faculty Author Q&A: Effie Rentzou on “Concepts of the World”

Effie Rentzou is Professor of French and Italian and Director of the Program in European Cultural Studies. Her book “Concepts of the World: The French Avant-Garde and the Idea of the International, 1910-1940” was published in September 2022 by Northwestern University Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

The very first time I thought of this book was as I moved from France to the USA. Going in and out of English, French, and Greek, often landed me in errors, rigid language, bafflement, multilingual dreams, interlinguistic puns, but also gave me a sense of endless expansion. This personal experience was projected on my long-term research interest, the historical avant-garde and the way these experimental writers and artists engaged with urgent political and social issues through their work. One of the most present issues was precisely what it meant to be international during the interwar period. The historical avant-garde movements were not only consciously international, actively pursuing to expand their activities beyond national confines and operating often on transnational networks; they were also fully conscious of the tightly interconnected world of modernity and thoroughly dedicated to producing conceptualizations and representations of what this world might be. What united these avant-garde movements is their common aspiration to the “world,” as their potential audience, as a terrain of expansion and action, and as object of representation. It is this latter that I wanted to explore: the world represented in the avant-garde work.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

This book went through many permutations. What I wanted to write initially was almost impossible – a complete account of international activities and projects of the avant-garde during a span of thirty years. Very quickly, though, I understood that what I really wanted to study was how artists and writers in Paris conceptualized the international and how they represented it. What did the world look like from interwar Paris for a poet like Apollinaire, or for a dadaist artist, or for the surrealist group? Paris morphed from the capital of the 19th century to an explosive hub of the historical avant-garde, a place of convergence for artists and writers from all over the world. The French avant-garde had Paris as its vantage point and the world as its horizon.

“Concepts of the World” became thus a book about this geographical imaginary, of conceptions of the world, deployed by writers and artists in and around such movements as futurism, Dada, and surrealism, as they were expressed in specific works and as they were informed by broader political, social, and cultural dynamics of the first half of the 20th century. Each of these conceptions has been encoded in terms that, while ostensibly embracing the whole world in the sense of the globe, historically developed as different interpretations of this totality. Internationalism, cosmopolitanism, and universalism have come to be used interchangeably in contemporary discussions of globalization.

I wanted to trace the differences among these terms, thereby establishing substantial and meaningful variations that have a considerable effect on the perception and the representation of the world. To imagine the world means to project a historical and political view on a geographical topos. Representations of the world are like snapshots that capture complex and multidirectional processes of historization, that is of interpreting the past, understanding the present, and gauging the future. In the book I present five such snapshots that together compose an interwar vision of the world.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

The book ends with the beginning of WWII; what I would like to explore next is the war’s impact on the avant-garde in France.

Why should people read this book?

The historical avant-garde is one episode in the deep history of globalization – the latest chapter of which we are all now experiencing. A few years into the new millennium, exuberant accounts of a global society maintained by free circulating people, goods, and ideas gave place to an increasingly bleak landscape of a globalization predicated on violent displacement of populations, economic exploitation, pandemics, and global surveillance. Understanding globalization in its historicity, in its mutations, contradictions, successes and failures, in one word in its dynamics, has thus become imperative.

Looking macroscopically at the avant-garde as an extensive lab elaborating different ideas and visions of the world permits for a vivid account of the historical push-and-pull of globalization, of desire to connect and hesitance for such interdependence. “Concepts of the World” constructs an alternative narrative of globalization, one that integrates resistance and discontent within this very process. In other words, the micronarratives of the book’s chapters complicate the grand narrative of modernity’s triumphant march toward globalization, of which the historical avant-garde (and modernism in general) is considered to be a decisive factor and proponent. Resistance and critique to the then existing geopolitical models of globalization – international capitalism, colonization, ideological dominance of the West, elite mobility – were in fact part of the avant-garde’s process of imagining the world. Reconstructing these processes may show how the path towards globalization was not smooth but striated, marked by the tug-of-war between the experience of the local and the aspiration to the global, a process that ultimately leads to the world.