The Global Ghetto: PIIRS Global Seminar Examines the History of the Jewish Ghetto

“The Global Ghetto” a summer 2024 PIIRS Global Seminar, The Global Ghetto, transported 13 Princeton students to Rome and Warsaw for six weeks of immersive instruction, during which they traced the history of Jewish ghettos from their origins in 16th-century Italy through the Nazi era.

“The students received an in-depth introduction to the history of the idea of the ghetto over five centuries, but they also came away with a greater understanding of how certain concepts, such as diaspora, racism, genocide, and exploitation, have helped to shape the modern experience across societies,” said instructor Mitchell Duneier, the Gerhard R. Andlinger ’52 Professor of Social Science, chair of the sociology department and author of the 2016 book Ghetto: The Invention of a Place, the History of an Idea.

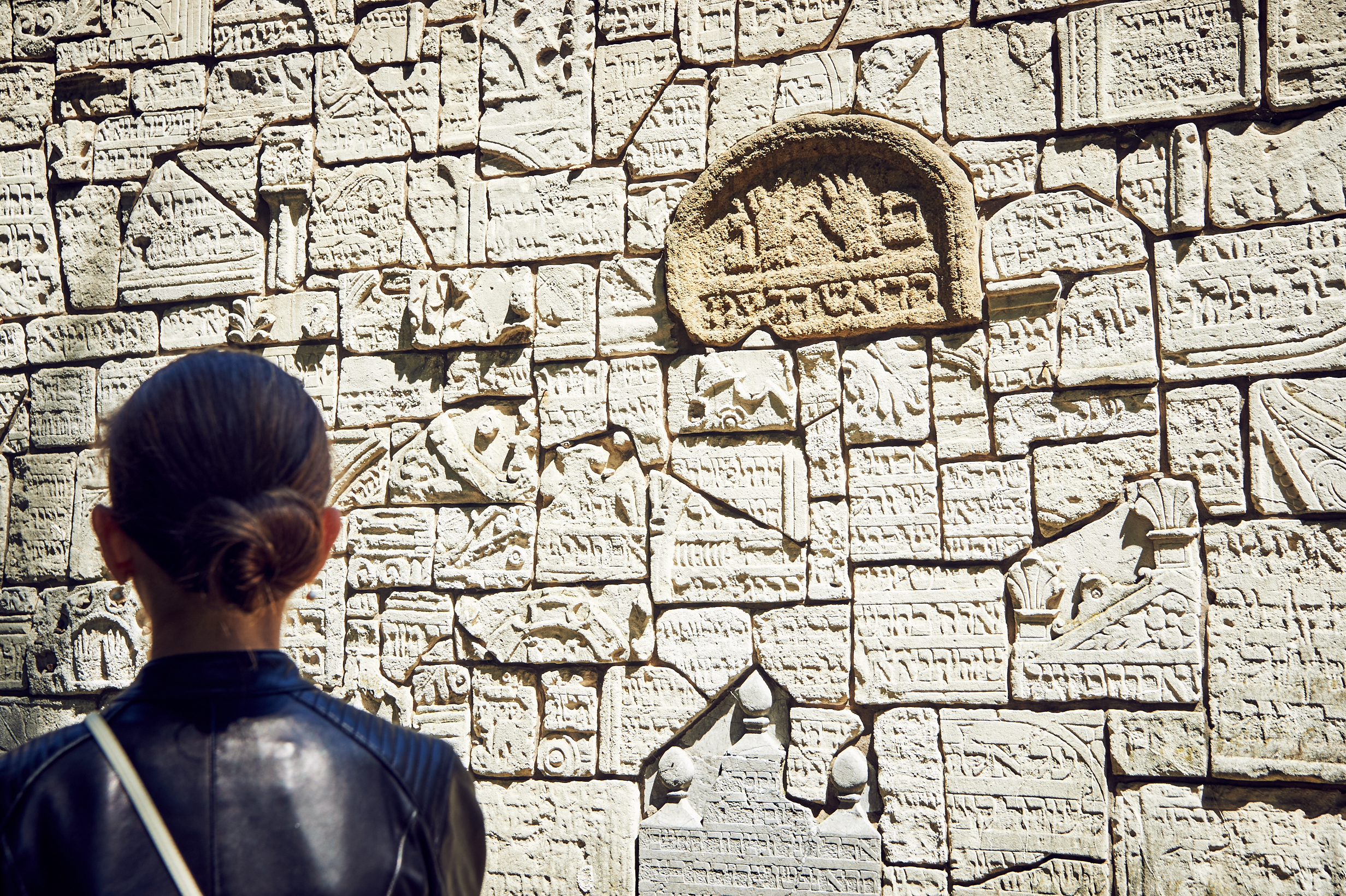

Duneier, along with his co-instructor Nathaniel Deutsch, Distinguished Professor and Baumgarten Endowed Chair in Jewish Studies and director of the Center for Jewish Studies at the University of California-Santa Cruz, and their students spent three weeks in Rome and three weeks in Warsaw. Here, the students studied history, Italian and Polish; screened films; and hosted speakers, including Italian historian Alessandro Portelli, Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer of the global black experience Ovie Carter, and Etan Michaeli, author of an award-winning history of Chicago’s Black newspaper The Defender. In Rome, these lessons were complemented by visits to the Vatican and to the Jewish ghetto, which was created by papal decree in 1555. As Deutsch pointed out, “The seminar traced the birth and spread of the ghetto, both as a series of historical sites and also as a metaphor and a social scientific concept that has really traveled around the globe.”

‘It felt more real’

The concept of the ghetto as we know it originated in Venice and Rome in the 16th century and gradually spread to many other European cities, where Jewish communities were segregated into ghettos, typically just a few square blocks in undesirable areas, until the 19th century. The motivation for their segregation was economic and theological; here, Jews could be separated from the rest of the population by physical walls, with limits placed on their freedom of movement and property ownership. In the years leading up to World War II, the Nazi regime once again designated certain neighborhoods throughout Europe as Jewish ghettos, from which they later often transported their residents into concentration camps.

For Blaise Stone ’26, a pre-med molecular biology major whose grandfather escaped the Holocaust by emigrating to the United States, the Global Seminar experience was highly personal. “It was a lot more emotional, not only because of my family background, but because it felt more real,” she said. “Being within the [ghettos] was just a lot more intense, and I felt more invested in the class.”

Shamma Pepper Fox ’25, a philosophy major, agreed. “On campus, it's easy to get bogged down in Firestone and get stuck in the classroom. This experience pops that bubble in a very real way,” he said. “There’s something about being in those spaces — visiting Auschwitz, seeing the museums, talking to Polish people — that made salient what would have otherwise remained abstract if we were in a classroom.”

In Warsaw, classes were held at the new POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, and the instructors led visits to Krakow’s intact Jewish ghetto, which dates to the Middle Ages. The group also visited the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, the site of the largest Nazi concentration camp, in which around 1 million Jews were killed during the war. “To see the traces and afterlives of these ghettos added a whole other dimension for our students that only this kind of course could,” Deutsch said.

The ghetto travels and transforms

Throughout the seminar, Duneier and Deutsch expanded on the concept of the ghetto, illustrating how its meaning and application had shifted across time and place. The term later came to be used for Black neighborhoods in the U.S., as well as Chinatowns, gay neighborhoods, and even the Gaza Strip.

“Ghetto as a concept continues to evolve and transform,” Duneier said. “We're mainly talking about the Early Modern period, the Nazi era, and the 20th century in the United States. But we're also talking about the current moment.” The question of Gaza and how to think of it in terms of the history of ghettos is a question that we have covered in this course for many years, but it had a particular timeliness this year.”

This robust, on-the-ground history lesson, accompanied by critical analysis, made this particular Global Seminar experience indelible and more relevant for the students.

“The seminar gave me the vocabulary to talk about very controversial things,” Pepper Fox said. “there are buzzwords these days around geopolitical events that carry a lot of emotion that can paralyze how I interact with those topics. Visting the sites of historical tragedy, reading sociological theory and learning how to think about certain things has helped me engage with current events and. has given me a stronger vocabulary for that.”