Looking Back to Pave the Way Forward

World Politics, a scholarly journal based at Princeton, celebrates its 75th anniversary in 2023. The Latin anniversarium contains a form of versus, which means “to turn” or “bend.” Appropriately, when we celebrate an anniversary, we do not turn away but toward the event in the past, to reminisce and to understand, to learn — all while looking toward the future. Much like Janus, the Roman god of endings and beginnings whose two faces point behind and ahead, we must look back to pave the way forward. To consider World Politics’ future, Princeton International spoke to some of its former editors about its past.

A brief recounting

Since its inception at Yale University in 1948, World Politics has been a preeminent journal of international relations. In its first issue, published in October 1948, World Politics included a pivotal research note by leading scholar Frederick S. Dunn on “The Scope of International Relations” as a field of scholarly inquiry and teaching. By the late-1950s, the journal had established itself as a prominent publication for international relations and comparative politics. Within these subfields, the journal published primarily qualitative work in the early years, said long-time editor and Princeton professor emeritus, Richard Falk. It wasn’t until the late 1970s and 1980s that World Politics began to publish quantitative research in political science, largely because “epistemological questions weren’t really discussed [in the academy] until the ’70s,” Falk said.

In 1951, not long after its founding, World Politics moved from Yale to the newly formed Center of International Studies (CIS) at Princeton. This move also played a role in what World Politics published. Michael Doyle, who was both the director of CIS and chair of World Politics’ editorial committee, explained that the World Politics founders had felt that Princeton was a better fit not only for their own outlook on scholarly research but also for their outlook on world politics. The founding editors “brought forward this idea that there was a semi-autonomous world of world politics that had to be understood on its own,” he said.

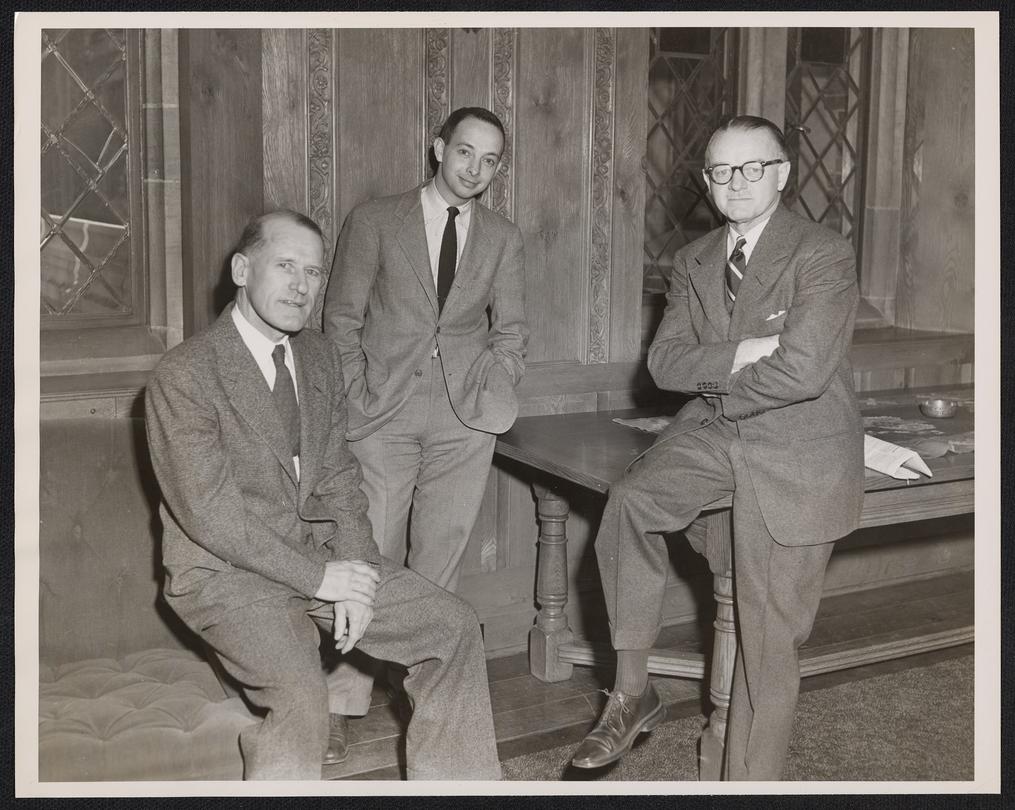

At Princeton, the journal took a more scholarly focus, as opposed to being policy prescriptive, but it remained a broad-interest journal — something that has perhaps always distinguished it from many of its counterparts. As former editor Henry Bienen said: “It was an eclectic journal. We didn’t turn ourselves into one thing.” And while the journal editors were Princeton based, Bienen explained that the editorial process remained undiluted. “There is no Princeton way of thinking about these issues.”

World Politics’ editorial process was one-of-a-kind, Doyle explained. Even after a full career in academia and government, Doyle described World Politics as one of the most democratic institutions he has ever been a part of — all editors participated and articles were published based on consensus. This democratic process remains today and distinguishes World Politics from its peers. Bienen and Doyle chaired World Politics at different times, but both oversaw the journal when it was central to CIS. Some years after Bienen and Doyle had moved on, CIS became PIIRS — the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies.

An enduring legacy

World Politics sits within PIIRS today. On Oct. 5, the chair of the World Politics’ editorial committee, Grigore Pop-Eleches, and senior editor Mark Beissinger brought together experts on Ukraine and Russia to discuss “The Politics of Russia’s War against Ukraine,” at the inaugural event in a series to celebrate the journal’s diamond jubilee. Pop- Eleches’ presentation drew on Russia Watcher, a survey project that he runs with a group of Princeton graduate students, which collects data at high frequencies on Russian public opinion about the war in Ukraine. “Given Russia’s increasingly repressive context, it is important to capture public opinion among ordinary citizens and to use these data to understand how military and political developments inside the country might influence mass political attitudes and behavior in real time,” Pop-Eleches said. Collecting such data is important, as former editor Oran R. Young recalls: “[during the Cold War] the science community [had to keep] channels of communication open when diplomatic channels were not working well.”

A month later, on Nov. 2, members of the journal’s editorial committee James Raymond Vreeland, professor of politics and international affairs at Princeton, and Kristopher Ramsay, professor of politics at Princeton, convened the second anniversary event: “Rise of China.” A day later, editor Rachel Beatty Riedl convened the final event in the series, “Democratic Backsliding and Resilience.” Riedl, the John S. Knight Professor of International Studies and a professor of government at Cornell, convened her event with her Cornell colleague and World Politics editorial board member, Kenneth Roberts. Nancy Bermeo, Nuffield Senior Fellow at Oxford University and long-time World Politics editor chaired Riedl and Roberts’ panel. Bermeo reminded the audience that “Democracies [have been and] are being disassembled but they can often be defended and reassembled too.”

The academic events bookended a meeting of the editorial committee, the first in-person meeting of the group since pre-pandemic times. The editors, panelists and other affiliates of the journal also gathered for a celebratory dinner on Nov. 2. At the events, the World Politics community looked both behind and ahead. Panel discussants recalled the past to understand and speak to the current contexts in countries around the world. The editorial committee engaged in a lively strategic discussion of the journal’s future. And at dinner, all were regaled with stories of the journal, now and then.

But while we today might feel tempted to focus only on the nostalgia or glamorize an imagined past, “scholarly research,” as Pop-Eleches said, “must continue to explain, through robust theoretical discussion and rigorous empirical analysis, how things work and why things happen.” World Politics will do just that.