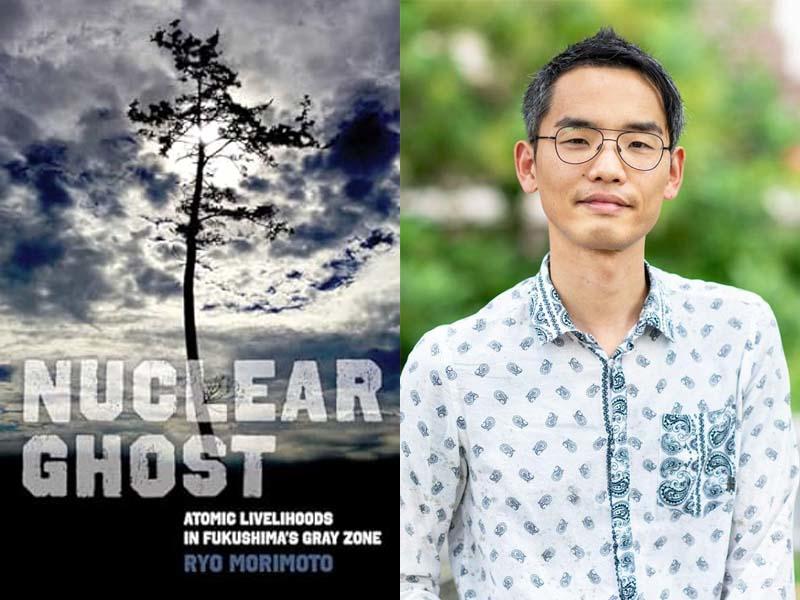

Faculty Author Q&A: Ryo Morimoto on “Nuclear Ghost”

Ryo Morimoto is Assistant Professor of Anthropology. His book, “Nuclear Ghost: Atomic Livelihoods in Fukushima’s Gray Zone” was published in April 2023 by University of California Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

I worked as a translator for a foreign documentary film on Fukushima that was filmed between 2012-14. This experience exposed me to the global imagination of the nuclear accident in Fukushima and narratives of the victimhood being expected from the residents in the region. As a translator, I had to mediate the negotiation between a foreign film director who wanted the world to know about the danger of the region and the residents who tried to tell the world how they had been living in the area despite the accident. Because of this, I felt that I had unique access to the interpretative misalignment and the moral duty to relay what had been witnessed. So, I decided to conduct a long-term ethnography to capture and tell the residents’ ongoing lives despite and because of the accident — the details that stayed outside of the director’s camera.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

I initially struggled to write this book mainly because the nuclear accident was (and still is) ongoing, and the regulations and policies in the region kept changing rapidly. The COVID-19 pandemic prevented me from visiting my field site, which actually helped me to think that I could write about the nuclear accident between 2013 and 2019. This limitation allowed me to focus on telling stories I had gathered during the period. Also, in 2020, I started the Nuclear Princeton project with a group of native undergraduate students. Collaborating with them helped me get new perspectives that I did not have before and expanded the analytical scope of my book from a Japan-focused one to a more transnational one.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

This book opened a path for me to explore the human-nuclear relationship further. Unlike the Chernobyl accident, the nuclear accident in coastal Fukushima produced many regions with low-dose radiation where residents continued living or returned to. With the Japanese government’s plan to reopen the evacuation zones, the accident created a situation where people are living close to the ground zero of a nuclear catastrophe, challenging the binary model of the human-nuclear relations of contamination and containment. My research explores how the production of actual or imagined distance from nuclear things leads to the proliferation of nuclear technologies. I am currently exploring the U.S.-Japan collaboration on developing a nuclear decommission robot that helps keep humans away from radioactive materials. I am interested in how this emerging technology will reinforce our imagined distance from contaminants and our belief that we can contain nuclear things.

Why should people read this book?

I think it is essential for us to learn from their experience since we tend to try to keep our distance from radiation and/or radioactive materials. This is true even though we collectively use nuclear energy or other nuclear-related technologies to improve our lives. The coastal Fukushima residents’ lives with radiation— though forced upon them— tell us that radiation is part and parcel of what it means to live in our already radioactive world and that we falsely imagine that only some people are exposed to radiation but not others, like believing that only Fukushima people are exposed but not the people outside of Fukushima. What coastal Fukushima residents’ stories allow us to see is that avoiding risks leads to burdens for others who tend to be less privileged. I like how one Japanese artist uses the phrase “the other side of the electric outlets” to encourage us to imagine the hidden connection between our lives and the lives of these residents. In this sense, since we benefit from nuclear energy, learning about those impacted by its generation is our collective responsibility.