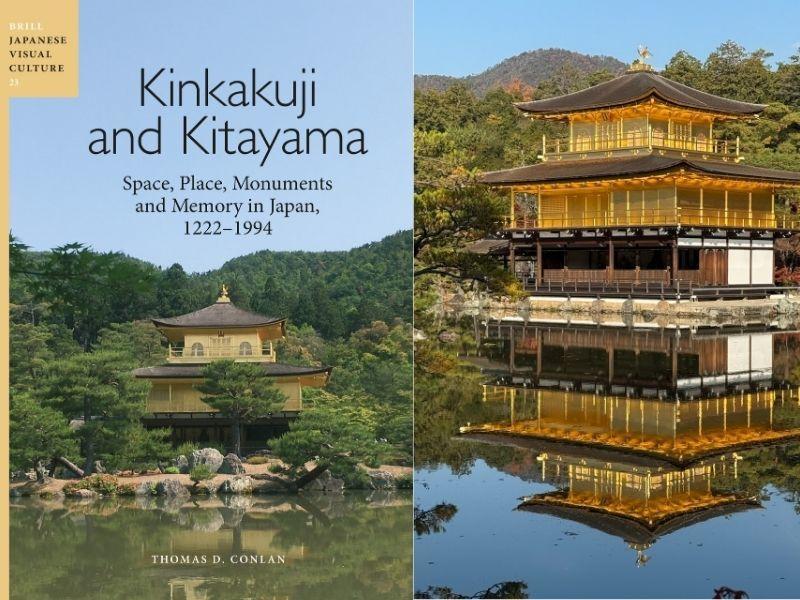

Faculty Author Q&A: Thomas D. Conlan on "Kinkakuji and Kitayama"

Thomas D. Conlan is a professor in the Departments of East Asian Studies and History. His latest book “Kinkakuji and Kitayama: Space, Place, Monuments and Memory in Japan, 1222–1994” was published in December 2025 by Brill.

How did you get the idea for this project?

I first visited Kinkakuji, one of the most famous tourist sites in Japan, in 1990, and at the time, I felt that the gleaming gold structure did not seem “real.” I visited Kinkakuji again in 2011 with my son, and in his company I experienced a sense of wonder about the place, and decided to write this book. I realized that because of its fame Kinkakuji has not been subject to careful study, and over the course of my research, I was surprised at how little understood Kitayama and Kinkakuji were.

How did the project develop or change throughout the research and writing process?

I first wanted to write a story of a place, Kitayama, and how people have perceived it over time. I was interested in why people perceived a particular area as being beautiful; what they did to alter that place to make it more beautiful; how they experienced and appreciated that area; and how books, prints, and photographs changed understandings of the place itself. All that content remains in the book, but I changed its framework and sought to understand the region through the monuments that were built there.

Influenced by the theories of Aloïs Riegl, I adopted a typology of intentional monuments, historical monuments, ancient monuments, and timeless monuments to describe how Kinkakuji, the Golden Pavilion, was created, preserved, destroyed, and rebuilt. After it was destroyed in 1950, Kinkakuji’s reconstruction ultimately came to influence how UNESCO authorities defined “original” monuments.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

The biggest question, and one that became clear to me only after years of writing this manuscript, concerns how understandings of authenticity have changed. Kinkakuji was built in the early fifteenth century, radically altered in the mid-sixteenth, and survived until 1950 as an “authentic” building even though much of it changed over time. After its 1950 destruction, it was rebuilt according to “traditional methods.” Within Japan, the structure was described as a reconstruction rather than a copy, and this influenced UNESCO definitions of authenticity in 1994. This monograph also highlights the difficulty of preserving a structure over time. I hope that other monuments and famous places will be studied taking into account these changing norms.

Why should people read this book?

The book is full of color illustrations ranging from panels of golden screens to woodblock prints, to photographs and printed images. Many are unique, while others are extremely rare. Together they reveal how a place and a monument were cherished and altered over time. Likewise, I hope that this book will cause people to reflect on how representations of a place influence how we perceive its “reality,” and how the example of Kinkakuji has shaped contemporary understandings of authenticity.

SOURCE