Kosba discusses race-consciousness of 1960s Egyptians in the African American imagination

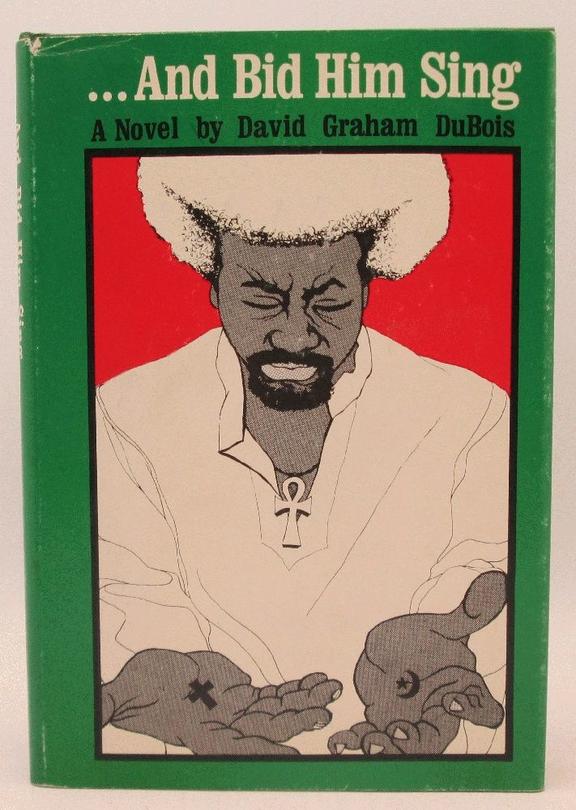

Can you translate race? Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies (PIIRS) postdoctoral research associate May Kosba wants to find out. To do so, she investigated African American intellectual David DuBois’ 1975 novel “…And Bid Him Sing” about his self-imposed exile in 1960s Cairo. DuBois sets up the novel as a Black diasporic internationalist discursive formation through which he draws the contours of Egyptian and African American “diasporian consciousness.” Kosba argues that the novel primarily grapples with issues of representation, including questions of displacement, authenticity, roots and routes, language, class and race.

“Keith Feldman [of the University of California-Berkeley] said the following in his articles: ‘African American political notions of Blackness do not translate in an Egyptian context,” she said. “That quote made me ask: Why does Black struggle with racism and white supremacy get lost in translation? Is it an issue of translation or is it is it something else?”

DuBois was the son of civil rights advocate W.E.B. DuBois. During his 12 years in Egypt, DuBois worked with Malcom X to establish the Cairo branch of the Organization of Afro-American Unity, which aimed to create solidarity between African Americans and people in the African continent. “[DuBois] was interested in solidarity work and allyship and questions of how to bring anticolonial activists together,” Kosba said.

According to Kosba, Egyptians were familiar with how they were perceived by white Europeans, but not by African Americans. “DuBois’ novel shows us the centrality of Egypt, Egyptian race consciousness, and racial identification in the African American imagination, and to what extent the Egyptians adhere to or diverge from these views,” she said.

For example, Egyptians perceived themselves in terms of religion or geography rather than race, Kosba explained. Meanwhile some African Americans, like DuBois, portrayed Egyptians as being part of a Pan-African collective.

“[In DuBois’ novel], there’s always the frustration with how Egyptians identify,” Kosba said. “They don’t always necessarily identify as African. It shows you the politics of African American ways of thinking about identity and where Egypt is in that conversation.”

Through its dialogues, DuBois’ novel teaches its readers about Egyptians and African American race consciousness. “The novel is deceptively easy, but it’s rich with ideas and relationships,” Kosba said. But it also has its limitations. “The Egyptian women are not very visible. The only woman that I can think of was a maid.”

The novel also neglects timely problems in Egyptian society, such as the displacement of the Nubians. British colonists initially displaced the Nubians by building the Aswan Low Dam in the early 20th century. In the 1960s and 1970s, Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser further displaced the Nubians when he built the Aswan High Dam as part of a nationalization campaign. “Nubian families did not only lose their land, but they also lost much of their cultural heritage,” Kosba explained. “While Nubians were expected to assimilate in Egyptian culture, they continue to live as a marginalized and racialized community.” DuBois’s novel is set in the 1960s, but skirts these events.

Kosba also described the differences in how DuBois portrays Egyptian characters and African American characters. “You don't see Egyptians in their fullness,” she said. “We see presentations of them and explanations of their consciousness. That's why translation is a big topic — translation and representation of consciousness, of ideas and of peoples’ existence.”