New study by PIIRS Postdoctoral Fellow shows state welfare reduces caste reliance, builds cross-group ties in India

Around the world, religious and ethnic groups have helped people deal with shocks to their lives and livelihoods for centuries. But ethnicity-based insurance operates through in-group reciprocity and solidarity, which can limit the formation of out-group ties and exacerbate ethnic divisions.

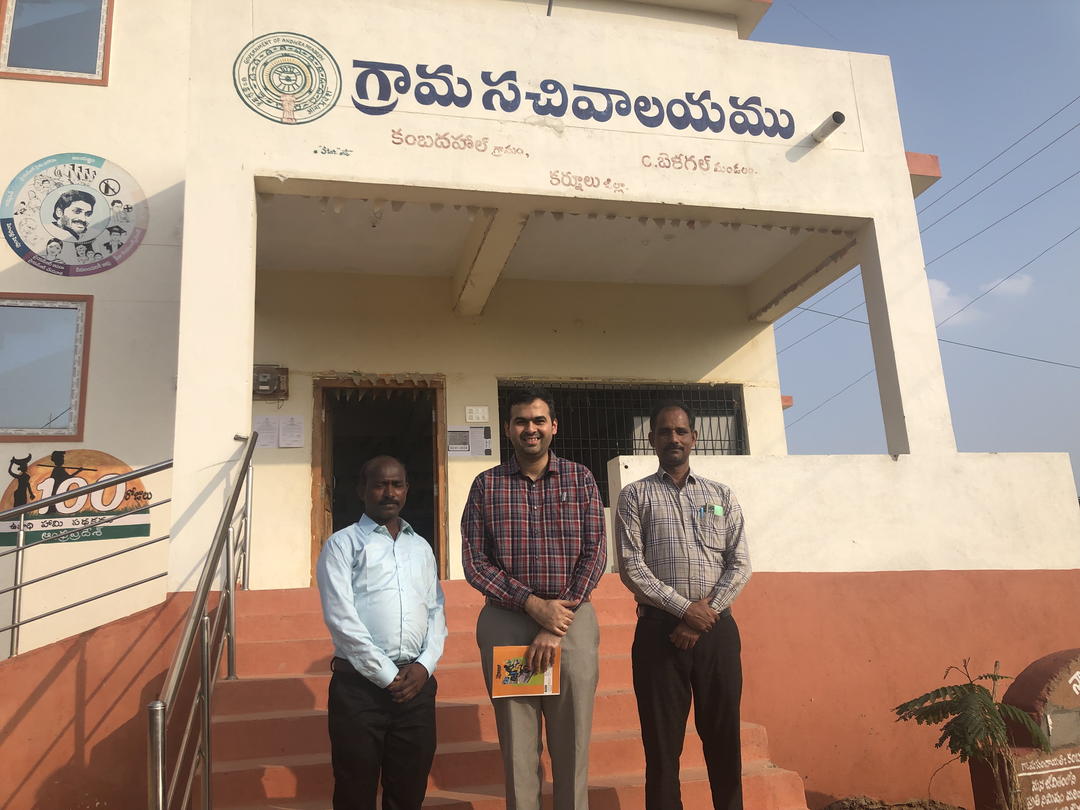

In a new study in American Political Science Review, Akshay Govind Dixit, a PIIRS Postdoctoral Fellow, asks whether a welfare state can promote social cohesion and tests this argument in caste networks in India. “Caste networks function as a safety net, which creates a dense web of obligations,” he said. “But these obligations have a cost. They tether people more tightly to their own group and make it harder to form productive ties with members of other groups. Caste norms can place real constraints on inter-caste interactions; adhering to those norms is harmful for social cohesion.”

In this study, Dixit focuses on an income support program for farmers implemented in the state of Telangana in India, the Rythu Bandhu Scheme (RBS). Launched in 2018, RBS provides residents of Telangana owning agricultural land with Rs. 10,000 per acre per year. Using panel data from 2,016 households, survey data from 3,020 households in 75 villages, and 56 qualitative interviews, Dixit concluded that the RBS program reduced borrowing from caste members significantly. “State-provided welfare increases intergroup ties by reducing people’s dependence on their own caste for support in times of need,” he said. “In the state of Telangana in India, when the government introduced an income-support program for farmers, households no longer needed to lean as heavily on their caste networks. This showed up clearly in the data: within-caste borrowing fell by about 38.5 percent. The economic ties that bind caste networks loosened in a measurable way. Crucially, where welfare reduced economic dependence on caste members, it also significantly increased inter-caste ties and interactions, showing that as in-group ties become less demanding, people engaged more across group lines.”

Dixit’s research has implications for how welfare shapes identity and ethnic politics in India and beyond. At PIIRS, he is currently working on a book examining how systems of risk sharing shape social order and identity politics. “We usually think of welfare as a tool for reducing poverty, but it also changes the fabric of everyday social life,” Dixit said. “The core insight of my article is that the ways in which people cope with risk — how they secure support against shocks to their income, health or livelihood — sustain the boundaries of solidarity within a society. When the state steps in as a reliable safety net, those boundaries can shift. For policymakers seeking to strengthen social cohesion, the results suggest that welfare can be a powerful tool.”

This study was supported by a Doctoral Dissertation Research Improvement Grant from the American Political Science Association and Stone Research Grants from the James M. and Cathleen D. Stone Program in Wealth Distribution, Inequality, and Social Policy at Harvard Kennedy School, as well as funding from the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, the Malcolm Wiener Center for Social Policy, and the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation.

The study “The Impact of Welfare on Intergroup Relations: Caste-Based Social Insurance and Social Integration in India” was published in the journal American Political Science Review on November 20, 2025. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055425101305