Droughts, political unrest in 6th century Arabia signify societal threat of extreme weather

The Arabian Peninsula experienced extreme dry conditions in the 6th century CE that — combined with political unrest and war — destabilized the region’s ruling power and ushered in nearly a century of upheaval and conflicts that reshaped the Middle East, according to new research led by researchers from Princeton University and the University of Basel in Switzerland.

The findings illustrate that while extreme weather events can be short-term, they can result in substantial, long-lasting political and socioeconomic disruptions — a critical lesson for today as climate change increases competition for water and other resources, said corresponding author John Haldon, Princeton’s Shelby Cullom Davis ’30 Professor of European History, Emeritus, and associated faculty in the High Meadows Environmental Institute (HMEI).

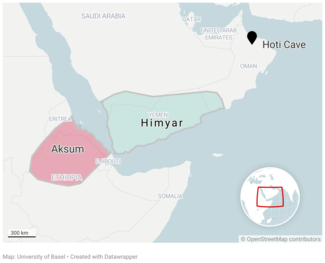

The researchers report in the journal Science the first evidence that a decades-long drought may have been a decisive factor in the downfall of the Himyarite Kingdom, which was located in present-day Yemen. The kingdom held regional hegemony for several centuries before entering a long period of crisis that culminated in its conquest in 525 CE. The next 50 years ushered in widespread political and social changes on the Arabian Peninsula that created the conditions from which Islam would emerge nearly a century after the drought’s peak, the study authors reported.

“There seems to be little doubt that an extended period of very severe aridity was an important contributing factor in the context of the upheavals in the Arabian world of the 6th century,” said Haldon, who is director of the Climate Change and History Research Initiative at Princeton.

The “society-environment-climate causality” also has been linked through paleoclimatic and archaeological data to significant social turbulence in prehistoric societies and the eastern Mediterranean basin in the 12th century BCE, Haldon said. In the 21st century, devastating droughts have resulted in mass migration out of the Middle East and North Africa, as well as exacerbated the economic, political and cultural inequities that spawned the ongoing Syrian civil war and the rise of the Islamic State, he said.

“Parallels between events of the 6th century and the conflicts over scarce pasture and diminishing water resources we see now — at least in respect to their larger destabilizing impacts — are hard to ignore,” Haldon said.

Petrified water acts as climate record

Traces of the Himyarite Kingdom can still be found today on the plateaus of present-day Yemen in the form of terraced fields and dams that formed part of a sophisticated irrigation system that transformed the semi-desert into fertile fields.

The researchers analyzed the layers of a stalagmite from the Al Hoota Cave in present-day Oman. The stalagmite’s growth rate and the chemical composition of its layers are directly related to how much precipitation fell above the cave. As a result, the shape and isotopic composition of the deposited layers of a stalagmite provided a valuable record of historical climate.

“Even with the naked eye, you can see from the stalagmite that there must have been a very dry period lasting several decades,” said co-corresponding author Dominik Fleitmann, professor of quaternary geology in the Department of Environmental Sciences at the University of Basel. “When less water drips onto the stalagmite, less of it runs down the sides. The stone grows with a smaller diameter than in years with a higher drip rate.”

Isotopic analysis of the stalagmites layers allowed the researchers to draw conclusions about annual rainfall during the time of Himyar. For example, they not only discovered that less rain fell over a longer period of time, but that there must have been an extreme drought. Based on the radioactive decay of uranium, the researchers were able to date this dry period to the early 6th century CE, though with an accuracy of only 30 years.

Fleitmann’s research group at Basel built on their isotopic analyses by examining additional climate reconstructions from the region and combing through historical sources. They collaborated with historians such as Haldon to narrow down the timeline of the extreme drought, which the researchers determined lasted several years. The full research team reviewed data that captured the plummeting water level of the Dead Sea and historical documents that described a years-long drought in the region starting around 520 CE, both of which coincided with the crisis in the Himyarite Kingdom.

“It was a bit like a murder case — we have a dead kingdom and are looking for the culprit. Step by step, the evidence brought us closer to the answer,” Fleitmann said. “Water was absolutely the most important resource. It is clear that a decrease in rainfall and especially several years of extreme drought could destabilize a vulnerable semi-desert kingdom.”

Furthermore, the kingdom’s irrigation systems required constant maintenance and repairs, which could only be achieved with tens of thousands of well-organized workers. The population of Himyar, stricken by water scarcity, was presumably no longer able to ensure this laborious maintenance, aggravating the situation further, Fleitmann said. The kingdom was further weakened by political unrest in its own territory and a war between its northern neighbors, the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires, that spilled over into Himyar. Himyar was primed to fall when its western neighbor Aksum finally invaded and conquered the realm.

Lessons from the past for today

Compared to ancient authorities, Haldon said, today’s policymakers have a much more sophisticated and nuanced understanding of the threats and risks facing a society’s stability. What still exist, however, are powerful interests that encourage short-term strategies to environmental stressors that can actually further reduce sustainability and resilience, leading to systemic crisis.

“Just as in the past, the ability of policymakers and political leaders today to appropriately plan continues to be determined by a range of cultural/ideological, political/structural and economic factors, including elite interests, many of which work to constrain or even discourage the implementation of potentially effective policies that could address both short-term challenges and mitigate future risks,” Haldon said. “This becomes particularly acute when these elite interests do not align with those of the far more numerous non-elites, who are significantly more likely to be affected.”

In today’s arid nations of Africa and the Middle East, the strategies societies developed over centuries to ensure sustainable regional and local economies are increasingly shunted aside by market-driven agriculture, as well as by demographic pressures and conflict over limited resources, Haldon said. The adaptive strategy of migrating to more hospitable lands is restricted by the colonial legacy of arbitrary national borders that force people exploit dwindling local resources beyond recovery, he said.

“Reversing the tendency toward structural socioeconomic imbalance in response to environmental challenges must be an objective that future policymakers place at the heart of their calculations,” Haldon said. “Because this sort of imbalance has generally been the case until now does not mean it has to be the case in the future.”

The paper, “Droughts and societal change: The environmental context for the emergence of Islam in late Antique Arabia,” was published June 16 in the journal Science. This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (PP002-110554/1 and CRSI22_132646/1), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41888101), the National Science Foundation (1701628), and the National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (DBI-1639145).

Angelika Jacobs at the University of Basel and Morgan Kelly in the High Meadows Environmental Institute at Princeton University contributed to this report.