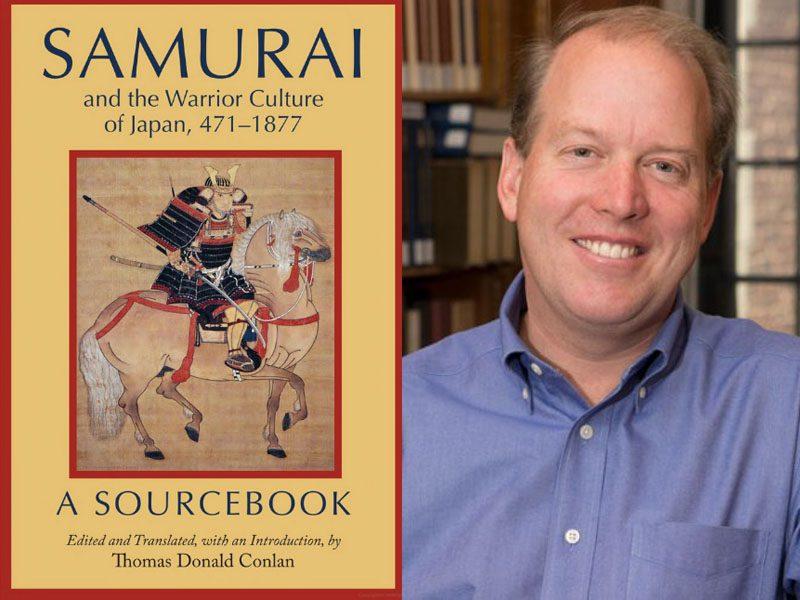

Faculty Author Q&A: Thomas Conlan on “Samurai and the Warrior Culture of Japan”

Thomas Conlan is Professor of East Asian Studies and History, and Director of the Program in East Asian Studies. His book, “Samurai and the Warrior Culture of Japan, 471–1877: A Sourcebook” was published as an eBook in March 2022, and in print in April 2022 by Hackett Publishing Company.

How did you get the idea for this project?

When still a graduate student, I started translating a variety of chronicles and documents for use in classes. I was, and remain amazed, at the richness of surviving Japanese sources, and the comparable absence of such works in English. I long had a desire to publish my translations. Rick Todhunter, of Hackett Press, wrote to me in September 2018, asking if I would be interested in doing a sourcebook about the samurai, and I jumped at the opportunity. I completed my proposal in April 2019 and when I visited Japan that summer, I inquired about possible sources, and was able to include some unusual items, such as five swords which contain inscriptions which constitute the oldest writing in Japan, dating from 471, and a ninth century sword which was buried with Japan’s first shogun, or “barbarian subduing general.” I also was able to include and image of a saddle and a cannon that were the possession of a warlord who converted to Christianity and became known as Otomo Francisco. Both have his identical FRCO monogram.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

I have long been interested in publishing a source reader. Once I was approached to do one for Japan in general, but I was asked to limit pre–1600 Japan to 100 pages. That was unacceptable to me. I thought that many more recent sources have been repeatedly translated, but accounts of those who fought when Japan was engulfed in civil war remained unknown. Some are humorous, others are touching, and still other surprising. For example, it is possible to know that guns first came into Japan in 1466, long before the first Europeans arrived on Japan’s shores in 1543.

For this project, I was asked to compile sources about the samurai and initially I had included materials idealizing warriors dating from the 20th century. The outside reviewers suggested that the book was too long, and I cut out everything post-dating the last uprisings by samurai in 1877. I was able to include many works, both noted translations from generous scholars such as Royall Tyler or Luke Roberts, and I also dusted off translations of chronicles, and my documents, as well as a remarkable cache of letters written by a warrior to his wife and son in the 1340s.

With the onset of COVID-19 and the cancellation of so many events, Yasufumi Horikawa, a visiting professor for the Tokyo Historiographical Institute, collaborated on translating several difficult law codes and other documents which have not been translated because of their difficulty. We completed the second ever translation of Japan’s 1232 law code, its “Magna Carta” as it were, and the first new translation of this important code since 1906! And other law codes of Japan’s Warring States Period (16th century) are translated here for the first time.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

How we understand the warrior culture of Japan, with an acknowledgement that very high rates of literacy existed. Likewise, hopefully people will better understand and appreciate the gulf in attitudes and behaviors between when warriors fought (pre–1600) and how they acted in times of peace. A third point is the role of court culture, rather than the battlefield, in promoting notions of loyalty service to a lord. And finally, the existence of a robust common law tradition in Japan changes how we understand the legal and social basis for medieval Japanese culture.

Why should people read this book?

It will give you a completely new viewpoint of Japanese history and allow you to come in direct contact with the lost voices of Japan’s samurai.